Why is this paper important for immunology today?

Zinc deficiency adversely affects immune function and response to infections, but very little is understood about how or why zinc is important for the human immune system. This paper [1] identifies a critical role for the zinc transporter, SLC39A/ Zip7, during early B cell development, thus directly linking zinc homeostasis to the immune system. This study by Anzilotti et al. is also a great example of how collaborations between clinicians and researchers fosters better understanding of the genetic and molecular basis of primary human immunodeficiencies.

How much did the functional imaging help you understand what was going on in the patients?

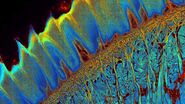

Using genetically encoded FRET/FLIM biosensors, we were able to image cytoplasmic and ER-retained zinc in primary B cells. This led us to the observation that hypomorphic mutations in Zip7 can disturb zinc homeostasis across cellular compartments. The functional zinc imaging was useful to support the hypothesis that the disturbed zinc balance might alter the localized kinase/phosphatase activity and hence impact cellular signalling and immune function in affected individuals.

What were the challenges you encountered to make these imaging experiments work? How did you manage to overcome them?

The FRET/FLIM microscopy setup was a completely new and unfamiliar technique for me. There were multiple challenges for our paper, including the establishment of primary CRISPR-Cas9 pre-B cell cultures, expression of the zinc biosensors in these primary cells, standardization of basic imaging conditions, such as optimal media and surfaces to keep the cells alive and adherent during the imaging period, etc. It took time and a lot of help from various colleagues from the Wellcome Centre for Human Genetics and the Cellular Imaging core, to overcome these difficulties. Finally, numerous trial and error sessions and far too many late nights at the microscope were critical in getting these experiments to work.

How familiar were you with lifetime imaging before starting this project? How difficult was it to do these acquisitions?

I had heard about the technique during seminars but had never used the microscope or the software previously and was a complete novice to it. Since every microscope and its specific software are often different, it was a sharp learning curve. however, once I was familiar with the microscope and software settings, it was much easier to do the acquisitions. It really helped that I had support from the core facility and they were able to help with setting up and optimizing the acquisition parameters.

What counsel would you give to someone trying to do similar functional experiments?

If you are a complete novice at using novel and cutting-edge microscopy tools, make sure that you have good training and guidance from people who know how to best use the microscope. You can always stretch boundaries and try new things once you know how to use the basic FRET/FLIM set-up. In addition, proper and accurate image acquisition is only one step and the actual data analysis and number-crunching are just as critical. These needed a lot of hands-on time and the data analysis was quite a labour intensive and slow process. Hopefully, as more and more non-expert first timers embrace this technique, there will be greater incentives to facilitate user-friendly and automated image data analysis.

How competent do you now feel about designing or running FLIM experiments? Do you intend to use this technique more?

After the initial work to assay intracellular zinc in cells, I have used the FRET/FLIM setup to measure the activity of small GTPases in primary B cells using genetically-encoded biosensors. While I anticipate that I will need technical assistance from time to time I expect to be able to independently set up and run the experiments as well as analyse the data with good confidence.