About Prof. Dr. med. Jan Maurer

Prof. Dr. med. Jan Maurer, Senior Consultant of the ENT clinic and Medical Director of the Catholic Hospital of Koblenz, Germany, has specialised, among other things, in special hearing implants such as the cochlea implant, and post-implantation rehabilitative therapy.

Prof. Maurer, who are the suitable candidates for a cochlea implant?

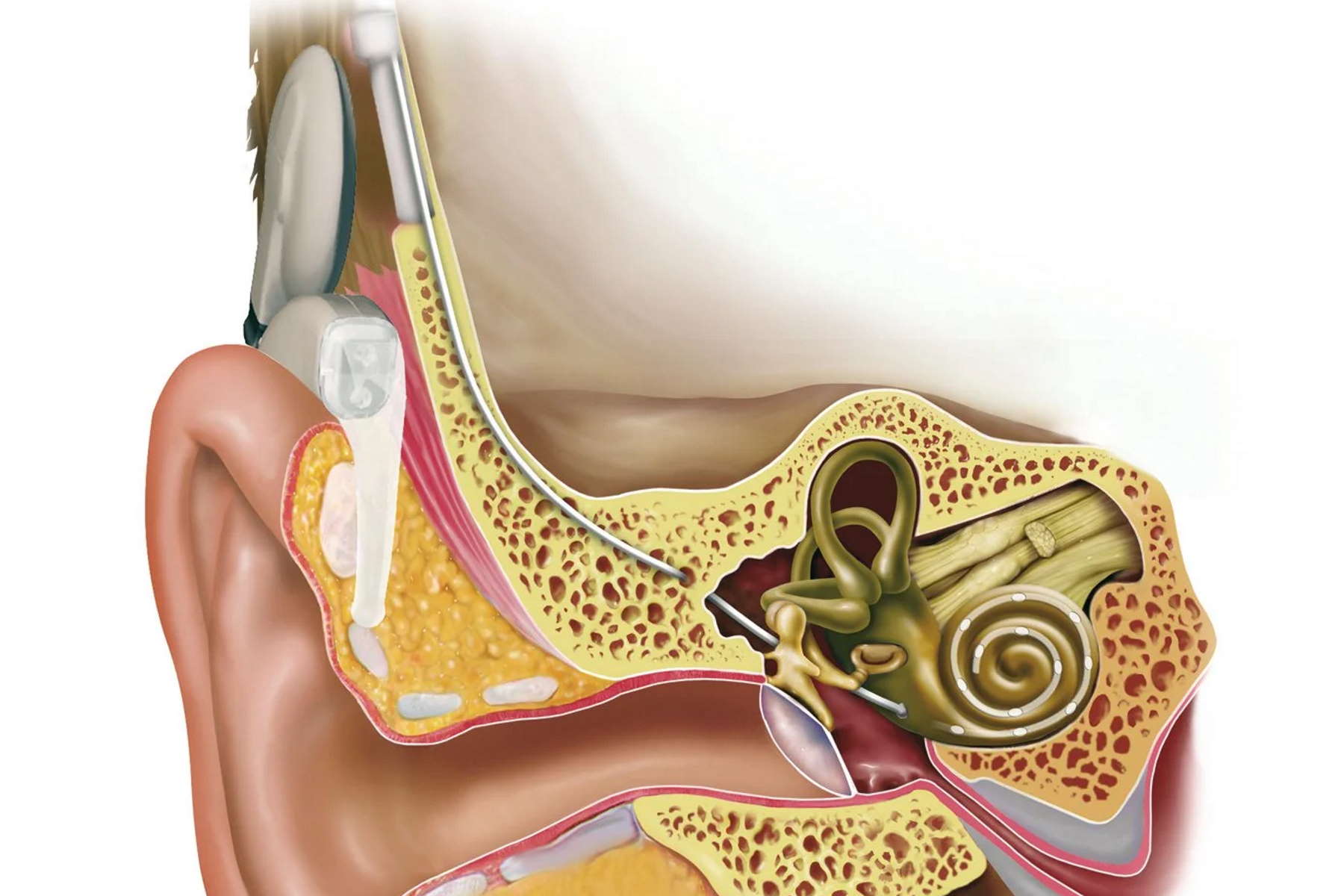

Most deaf and nearby deaf people needing more than a conventional hearing aid still have an intact auditory nerve. These patients can benefit from an inner ear implant, or cochlea implant (CI) as it is called. The indication is determined by special hearing tests, diagnostic imaging of the petrous bone and testing of the auditory nerve function. In addition, the history and duration of the hearing loss are key factors for successful rehabilitation.

Cochlea implant patients have to learn to hear all over again.

Children who were born deaf can lead a practically normal life with this implant, provided surgery is performed as soon as possible around the first 12 months. The sooner adults receive an implant after losing their hearing, the higher the chances of success. After more than ten years of deafness, it is unlikely to be successful. Patients with a damaged auditory nerve can be given a so-called auditory brainstem implant. This works in a similar way to a CI, except that here the first hearing centres are electrically stimulated in the brainstem.

Is there an age limit for a CI?

Speech and hearing develop in parallel very early on in childhood. Deaf children should receive a hearing implant before their 4th year of age – before the centres of speech are fully developed. After that, the chance of learning to speak naturally decreases. We fit implants in children of around one year of age. Our youngest CI patients are eight months old. At the other end of the scale, there is no numeric age limit. My oldest patient was 86, now he’s 94. The implant has enabled him to continue looking after his invalid wife at home. Before he had the implant, his deafness made it almost impossible for him to cope with everyday things such as shopping.

Our youngest CI patients are eight months old, my oldest patient was 86.

Are always both ears provided with a CI?

Even people who were deaf in both ears used to receive only one CI, just as people who were hard of hearing only used to receive one hearing aid. Today we know how important bilateral, stereophonic hearing is for spatial orientation and hearing in noise, for example. It has long been the norm to fit hearing aids in both ears. And more and more countries are gradually adopting bilateral CI implants as standard procedure.

Although this is naturally a positive development in general, I do see a certain risk of cost explosion, as there are a great many people who are deaf in only one ear. It is simply a matter of assessing each case individually. A CI costs around 20,000 Euros and a further 15,000 to 30,000 Euros are spent for diagnostics, surgery, and rehabilitation.

How important is rehabilitation?

The hearing impression with a CI is completely different from normal hearing. You have to bear in mind there are about 20 electrodes to replace approximately 30,000 highly sensitive hair cells with 100 sensory hairs each in the cochlea. The hair cells enable us to finely differentiate sounds by transforming the oscillations of the inner ear fluid, which are generated by sound waves of differing amplitude and frequency, into electric impulses and relaying them to the auditory nerve. Despite the ongoing improvements in hearing implant technology and refinement of stimulation possibilities and speech coding, an implant is not a full substitute for the loss of hearing.

Therefore, rehabilitation is extremely important, especially for deaf children so that they can learn to speak as freely and normally as possible. Adult patients have to learn to hear all over again. The CI is first set about four weeks after surgery has taken place. Although patients can hear sounds and noises, they don’t know what they’re hearing. They have to acquire completely new hearing skills and need time and patience to regain their communication competence.

This arduous process can take up to two years. It’s comparable to learning a new language. However, the brain is flexible when it comes to processing acoustic stimuli and adapts well to the new perceptual situation. I have even had patients who went for a walk a few hours after the CI was first set and already began to understand what the "new" world sounds like.

During surgery already, we are able to determine whether the CI is in contact with the auditory nerve, and we can measure how strong a stimulus has to be for it to be transmitted by the auditory nerve. These parameters are particularly important for the first setting of the CI in small children. After all, they are not able to say whether a sound is too loud or too quiet. So we start with really quiet stimuli and carefully build them up until we reach the optimum setting.

What role does the surgical microscope play in your work?

The trend towards miniaturised accesses in nearly all areas of ENT surgery means extremely small fields of view. For example, we can’t drill the 1 mm hole in the cochlea to fix the electrodes for a CI without using a microscope. As well as optical quality, I need good field depth and optimal illumination, particularly for deep and narrow surgical approaches. The instrument must also always be ready to operate, easy to use and adjust for all those involved. I do between 25 and 30 hours of surgery a week, which would be unbearable without an ergonomically adaptable microscope. We are highly satisfied with the systems of Leica Microsystems in all these points.

How would you like to see a surgical microscope of the future?

I would find it extremely useful to have a microscope I could combine with an endoscope, maybe using an attachment. For paranasal sinus surgery for example – I do this with a microscope, but I then use an endoscope to check all the corners to make sure everything is clean. An issue that is gaining general significance is the integration of the various imaging techniques. Considerable progress has been made here in the last few years, but there is still vast potential for future innovations.