Penelope Zorzi

Dr. Penelope Zorzi is Product Workflow Manager Health and Clinical Microscopy at Leica Microsystems. She holds a doctorate in Biomedical Science from the University of Verona, Italy and completed her post-doc at the University of Washington in Seattle, USA. She has a decade of experience working as a research scientist and project manager in immunology, genomics as well as pathology. Following a first experience in cancer immunotherapies in pharmaceuticals, she decided to move into marketing and sales, received training in digital marketing in Milan, Italy and in data-driven marketing at Stanford University in California, USA. In most recent years, she completed a product management certification from Product School of Seattle, participated in a Data Science Bootcamp, and held a product management position in design and building materials. Currently, Dr. Zorzi is part of the Applied Business Unit at Leica Microsystems, where she collaborates with product development and is responsible for providing insights on pain points and needs of internal and external target groups as well as industry expertise and knowledge.

What is the biggest challenge pathologists face?

Dr. Zorzi: The time to diagnosis is crucial in clinical pathology. Just think about histological analyses during surgery. Pathologists look at frozen tissue sections which have been created form a biopsy taken from a patient who is still in the operating room. The pathologist’s diagnosis will influence the surgeon’s further course of action.

This is a great responsibility.

Dr. Zorzi: Absolutely! Their diagnosis needs to be accurate. From my experience, pathologists are very conscious of the impact their diagnoses have and will, in case of any doubt, always consult a colleague. Some labs have multi-view microscopes for this purpose, so that two people or even more, if it comes to teaching, can share the same view of the specimen, or use images acquired with a camera for that purpose.

Can you take us into the details of a pathologist’s microscopy work?

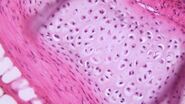

Dr. Zorzi: Pathologists, depending on their specialization, will look at tissue sections and fluids. To be able to look at these specimens, lab technicians or pathologists either freeze the samples or fix them, e.g., in formalin, and cut them into thin slices using a cryostat or microtome, respectively. For examination under the microscope, the sections are put on a glass slide, stained, and cover slipped. Fluids mostly take the form of smears on the glass slide and are covered with a cover slip as well to prevent contamination and improve image quality.

Where do the specimens originate?

Dr. Zorzi: Specimens originate from all parts of the human body. Tissue stems from surgeries or biopsies. In histopathology, tissue specimens may, e.g., be excised moles for checking on melanoma skin cancer, breast tissue biopsies for cancer checks, or even whole organ biopsies after procedures, such as hysterectomies, colectomies, or tonsillectomies. Bone may be looked at to diagnose cancer or other bone diseases, such as osteoporosis. In cytopathology, cells are the center of attention. They can be exfoliated, scraped from tissues, or taken with fine needle aspiration. The cells can also stem from fluids, pap smear tests by gynecologists, or sputum specimens which pulmonary specialists hand in for diagnosis of different cancers and infections. Hematopathologists will look at whole blood, lymphatic fluid, or bone marrow for diagnosis of infections, anemia, blood-clotting disorders, and leukemia. And last, but not least, medical microbiologists look at microorganisms to diagnose infections.

What do pathologists look for in their specimens?

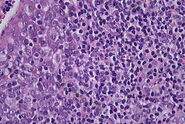

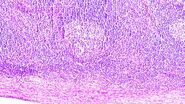

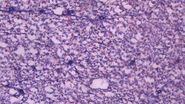

Dr. Zorzi: In general, they look for deviations from the norm. Structures, shapes, and colors, as well as the number of cells, can be an indicator of abnormality and thereby disease in a specimen.

Can you give us some examples?

Dr. Zorzi: To find pathological alterations, tissue specimens are commonly stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin, H&E for short, while cytopathological specimens are often stained with papanicolaou. The uptake and intensity of a stain enlightens pathologists about the type and severity of cancer as different parts of the tissue or cell take on different colors. Another example is counting the number of white blood cells and looking at their morphology in whole blood samples which helps to diagnose leukemia.

How does the microscope help them to see what they need to see?

Dr. Zorzi: The first aspect is magnification. The microscope makes more details visible than the naked eye could discern. Very often, pathologists gain a quick overview of the specimen with a low magnification, identify an area of interest, move the stage there, and switch to a higher magnification to look at the details.

The second aspect is the color reproduction and clarity of the image. As the uptake and intensity of the stains in specimens is important for the diagnosis, truthful color reproduction and good differentiation of various morphological or cytological elements is crucial for pathologists to draw the right conclusions from what they see.

The third aspect is the option to view the specimens with different contrast methods. Brightfield is used to look at stained slides for differentiation of the staining. Phase contrast makes cell or tissue structures visible in unstained specimens. Several other contrast methods can be used for very specific analyses, e.g., polarization contrast helps in the detection of crystals and amyloid whereas fluorescence in situ hybridization, FISH for short, is used to visually assess some DNA alterations.

Which roles do cameras play in pathology?

Dr. Zorzi: Cameras have become more important, especially since they facilitate documentation. Leica microscopes for clinical pathology come with the option to attach a camera and the suitable software, called LAS X, which allows pathologists to take images and annotate them directly in the software. They can share images with colleagues for second opinions, which is helpful if no multi-view microscope is available, or if the consultant is located in another hospital or country. Also, they can easily go back to existing images when a second biopsy of a patient comes in, rather than retrieving the archived glass slide.

How do cameras interact with a laboratory or hospital information system?

Dr. Zorzi: Many cameras have a TWAIN driver to connect them to any existing information system. The LAS X software is used to acquire the image and annotate it, but the image is accessible via the laboratory or hospital information system.

You mentioned time to diagnosis as a crucial factor. Which effect does the pressure of time and responsibility have on pathologists?

Dr. Zorzi: Pathologists often feel tired from their work, because they spend long hours looking through the eyepieces of a microscope. This may cause strain in the eyes, neck, and back, but also in the hands and arms which can be caused by repetitive movements, so their muscles may feel tense during or at the end of a workday. Additional pressure from a high workload or particularly difficult specimens may come on top of this and leave them fatigued.

How can a lab environment contribute to relieving physical strain?

Dr. Zorzi: Ergonomic microscopes can do a lot for the workforce. Microscopes which can be adapted to the pathologists’ physique help them to work in a more comfortable posture. I’ve seen the positive effect many times in labs I visited. Strangely enough, uncomfortable postures are something many pathologists put up with for a long time. But as soon as they work with an ergonomic microscope where they can adjust the height and tilt of the oculars, work with straight shoulders thanks to a symmetrical setup, and adapt controls to suit their preferences as a right- or a left-hander, they directly feel the difference and cannot imagine how they coped before.

Does efficiency figure in pathology?

Dr. Zorzi: Efficiency plays a major role in pathology. Besides the pathologists’ level of experience, efficiency has a lot to do with ergonomics and microscope design as well. It’s not an obvious connection, but if you consider that examinations require many small steps which add up, the connection becomes clear. For example, if we look at magnification changes, each hand movement, each movement of the objective revolver, and each stage movement takes time. The less time these movements take, the more smoothly the revolver moves, the more precise the stage can be set, then the shorter the time to diagnosis.